Moving Away from "Schoolishness" Towards "Joyful Learning"

A Q&A with Susan Blum on her new book.

One of the distinctions I often draw in thinking about engagement and education is that there is a difference between “learning” and “doing school.”

Learning is, you know, learning. Doing school is engaging in the behaviors that result in satisfying the demands of a system built around proficiencies as determined by assessing the end products of a process. You can successfully do school without learning much of anything. At least that was my experience through many periods of my own schooling.

My belief is that organizing schooling around doing school is part, a big part, of the current problem of student disengagement. When classwork is purely an instrument for getting a grade and moving on to the next check box, learning becomes incidental. It may happen, but it doesn’t have to happen.

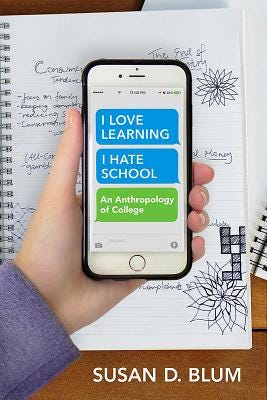

One of the most important books I read that helped me think about these distinctions is Susan Blum’s I Love Learning; I Hate School: An Anthropology of College. Blum, a professor of anthropology at Notre Dame saw that ways her highly prepared, driven, intelligent and curious students felt essentially alienated from the experience of schooling and went digging for insights like a good anthropologist. I ended up making significant use of her findings in my book, Why They Can’t Write because so much of what she found was reflected in what my students had to say about their experiences of writing in school contexts.

Professor Blum has continued her explorations of how and why students find school so alienating in her edited collection, Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead), and now in a new book, Schoolishness: Alienated Education and the Quest for Authentic, Joyful Learning.

She was gracious enough to answer some of my questions over email about what “schoolishness" is, how it harms students, and how teachers and instructors can work through a process to move away from schoolishness, and toward learning.

John Warner: I sort of want to walk through some ideas together, but just as some starting background, what’s the definition of “schoolishness” and why is it something we should be aware of and concerned about?

Susan Blum: “Schoolishness” is the characteristic of being made for, by, and about school. It is the quality of being disconnected from things outside school. Things that exist only within the context of school, such as multiple-choice tests, are schoolish. In the book I highlight ten dimensions of schoolishness, as they exist in conventional schools, and in each case I offer less-schoolish alternatives, whether mine or those of others.

JW: One of my personal obsessions is thinking about the difference between “learning” and “doing school” where doing school is essentially just a series of behaviors designed to achieve the desired grade with the minimal necessary effort. This seems counterproductive on its face, but you say it’s even deeper than that.

SB: Given how much time, energy, and money nearly everyone in our world spends in school, this “doing school,” as Denise Pope called it, is tragic. Students have learned to imitate learning; to provide a performance, a facsimile of whatever each teacher demands as evidence of learning. So much of what we do in schools doesn’t work, whether by “work” we mean learn or thrive or prepare for a competent, meaningful life beyond school. The central organizing concept for me was a contrast between alienation, brought about by numerous sorts of disconnections, such as doing things only because of coercion, and authenticity, which is connection, meaning, genuineness, and even use.

JW: I know from reading your books that you, personally, really liked school? What did you like about it? Why do you think school worked for you?

SB: School rewards solitary, individual, abstract learning of self-contained subjects, with finite amounts of knowledge and information, measurable and assessable. Much of it seems unconnected to the rest of people’s experience. But I did love academic learning, the kind you get from reading, homework, tests. It worked for me. Through that solitary reading I discovered greatly fascinating things, through all the required academic subjects, whether math or foreign languages or literature, science, and later philosophy and the careful thinking that it enabled. Later I discovered China and Chinese, and anthropology, I especially loved the beauty and meaning with which all humans imbue their experience. I loved knowing that things could be different from how they are.

You can see, from this, that I loved the intellectual content and took it seriously.

I think it worked for me because I have a pretty good attention span, I can—or I used to be able to—sit alone for hours. I can focus. I had a lot of other advantages, such as a secure home and good health. I am a native speaker of “standardized” American English, and am from a middle-class white background. I like abstraction and imagination.

I liked graduate school the best—which figures, since it’s the deepest and most academic.

JW: What you describe above, really shouldn’t be too divorced from what students could do in school, but it really does seem kind of foreign to how schools are structured.

SB: There are many things I didn’t mention here, such as forcing students to learn and do things that they had no interest in, and forcing them to follow arbitrary rules, and making everything the same for everybody. As schools are structured, they work for the minority of people who are like me. But they don’t work for most students. Most people like to move around, and use what they’re learning, and they aren’t content to learn alone from reading. Abstraction isn’t easy or natural for most humans. I’m not saying everyone should just do whatever they want, what is easy or comfortable, but there is a huge amount of evidence that beginning where learners are and working with them, rather than against them, is both more effective and more humane. There’s a concept of “self-directed education” which is a reminder that coercion is not always needed to get students to do hard work and learn deeply.

JW: At Inside Higher Ed and in my book I’ve written a lot about how, why, and when my thinking evolved around what I was doing in teaching writing, and you lay out some of your journey in your books, but given that we’re talking to a lot of teachers here, I was hoping you could share the stages you went through as your thinking evolved and even how you reacted through those stages. One of the realities I try to reinforce when I talk to folks about changing their pedagogies is that nothing happens all at once. It’s always a journey. Was it like that for you?

SB: Oh my goodness. You should have seen the judgmental approach I brought to my early teaching! I thought there was one right way to learn, and if only I could get everyone to do it, they would learn a lot. It is a little embarrassing now to remember this. I used to join the faculty sport of complaining about students: “Can you believe they wrote X?”

I was a strict grader, and I really liked the control I had over all the numbers. I thought that academic writing was the goal, and that there was a single way to do it. Gradually, every dimension of my teaching changed, to the point that I no longer even call myself a teacher, but rather, a “coach.” I don’t want to control everything. I want to help my students become confident, independent learners, different from each other, as they come from different places, in different bodies and identities, have different experiences even in the same place, and then head off to different futures. Why should the goals be identical? So I ask my students to reflect on their own goals, beyond requirements and credits.

JW: I think one of the things you illustrate here is that like writing, or even learning in general, teaching is a process and we should expect it to evolve over time. But how can we re-frame what we’re doing in a way that allows us to engage that process and make those changes?

SB: When I give talks about pedagogy, I encourage people to start small. I think one of the best places to start is to ask students to reflect on their own learning. In my classes, students include a “reflection” with most of their major work. Some people call this “self-assessment,” but I really want it to be more rumination and less judgment.

It’s important to keep the biggest possible goals in mind: what do the learners need in their lives? How do our activities help with that? I’ve really questioned every single dimension of my pedagogy, and my classes don’t look at all like the ones I taught even ten years, and certainly thirty, years ago.

I encourage us to find a way to make each activity compelling in its own right: why might this be something a learner would do on their own, not just because we’re making them do it (for a grade)? This is really the hardest part. We are so used to threatening with bad grades or rewarding with points (as Alfie Kohn warns us not to do in Punished by Rewards or “From Degrading to De-Grading”), that we have not done the constant hard work of figuring out activities, including reading, writing, discussing, labs, projects, small-group activities, that are in and of themselves valuable and enticing. I know this sounds idealistic. But as I’ve worked to create such conditions—and it’s not always immediately successful, and what works with one batch of students doesn’t always work with another—I’ve witnessed breathtaking examples of student enthusiasm and engagement. I’ve become more idealistic about their natural capacity for learning and wondering—a capacity that has often been squelched by schoolishness.

JW: This is one of the things I try to emphasize when I talk to folks about evolving their teaching practices, that it takes time and also to be forgiving of themselves when the experiments don’t go as planned. What do you recommend in terms of mindset and strategy to keep the process going?

SB: I struggled for years to write this book and to figure out how to convey a critique-with-alternatives that was not mere listing of things wrong but a coherent critique of the entire institution, globally, as we have come to accept it. In anthropology we often talk of our job as “making the strange familiar,” such as going to remote locations and making sense of the initially odd things we encounter, and then “making the familiar strange,” which is to then question what has become so obvious, naturalized, that we don’t even ask about it. For me, the strangeness of schoolishness took me decades to understand.

One of the most essential dimensions was talking honestly and openly with my students as partners about their experiences, and deeply observing what their experiences are like. In this sense, I’ve been an anthropologist, and ethnographer, of school. But this became truly possible only once I released my inherited sense that my primary task was judgment.

My interactions with students are so much more satisfying and enjoyable now. I truly see us as engaged in a partnership to help them in ways that are meaningful to them and, as much as possible, enjoyable. In the title of my book I posit a possibility of “authentic, joyful learning,” but I’m also deliberate in calling it a “quest,” not a completed, once-and-for-all accomplishment.

I see our current moment as involving a struggle between automating a uniform pre-packaged version of “learning,” emulated by both learners and teachers with the assistance of AI, and a genuine, humane, meaningful, always-contextual version of learning.

I know which side I’m on!

The term ‘accidental learning’ is something I tried to achieve as a teacher. I often found students retained the content better if they almost didn’t realise they were learning.

It is troubling to me to hear that Akilah Richards’ work was not known to this author, as Akilah has been a prominent leader in the self-directed space for many years. I’m also troubled to see that a Black woman’s work has been overtaken by a white academic‘s book. schoolishness.com (Akilah’s website, rich with resources for those wanting to delve into deschooling and liberation work) is now buried in Google searches underneath articles about this new book. This erasure of Black women’s voices is unacceptable.