In my view, if you want to get students - or anyone for that matter - engaged with the act of writing, you need to give them sufficient freedom to write in ways that are interesting to them while putting at least some stakes (not grades, per se, but a larger purpose) around the work.

At the same time, total freedom, a blank page and instructions to “Write whatever you want,” is likely to result in very little writing for most people. Confronted with infinite choice, the problem of how to initiate becomes overwhelmingly difficult.

The benefits of structure in fostering engagement have been observed across many different domains. If you watch two children engaging in cooperative imaginative play, one of the first things they will do is start drawing boundaries around what’s allowed in order to move the shared experience forward.

Limits allow for the focusing of activity around a definable, and in turn accomplishable purpose. There is a starting point, a journey, and a destination.

It’s important to recognize that if learning is the goal, the experience needs to strike a balance between freedom and structure. Over time, in my own teaching I lost sight of the goal of learning, by substituting getting a good grade on my assignment rubric for the experience of learning. This led me towards an extremely prescriptive approach to teaching writing where I attempted to atomize the process down to the paragraph and even sentence level, essentially a more sophisticated version of the five-paragraph essay that many students had experienced prior to college.

I was denying students the experiences that would allow them to learn by trying to constrain them to a march through a progression that was oriented around school, rather than learning.

My explorations after my epiphany resulted in a pedagogy that is defined by something I call the writer’s practice (the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and habits-of-mind” of writers), and in teaching inside the practice, I’ve come to appreciate the necessity and difficulty of creating productive constraints.

My book of curriculum, The Writer’s Practice, is a collection of highly structured experiences, which are also, hopefully, designed to give students significant freedom inside those experiences to write about subjects and ideas and new knowledge in ways that allow them to develop their practices. Using my curriculum and witnessing how it is used by others has made me particularly sensitive to finding this balance between structure and freedom as a way to foster engagement.

One of the reasons I was interested in working with Frankenstories1 is because the first time I played the game I experienced a great example of freedom and structure working in tandem, and could see immediate connections to multiple dimensions of the writer’s practice.

Frankenstories is at heart a game, but like all well-designed games there is an underlying gestalt that delivers a purposeful and meaningful experience and that meaning is found in the structure.

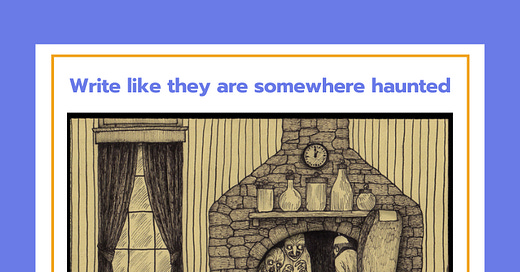

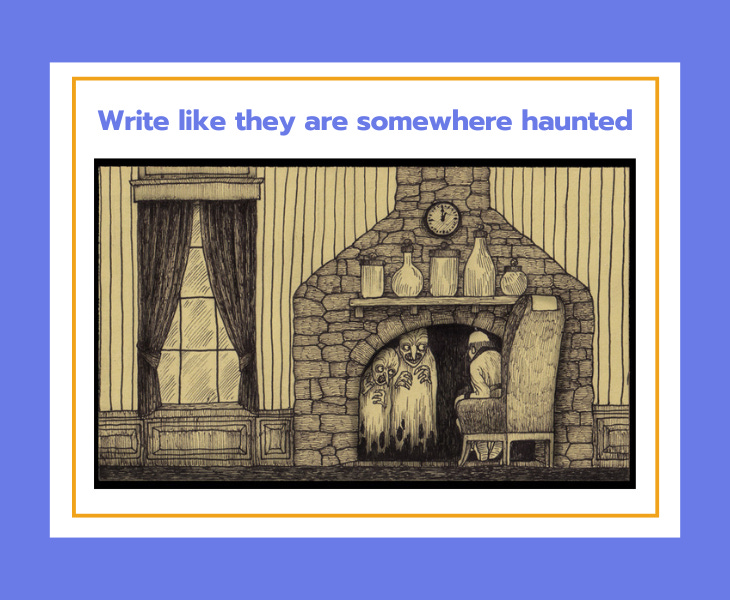

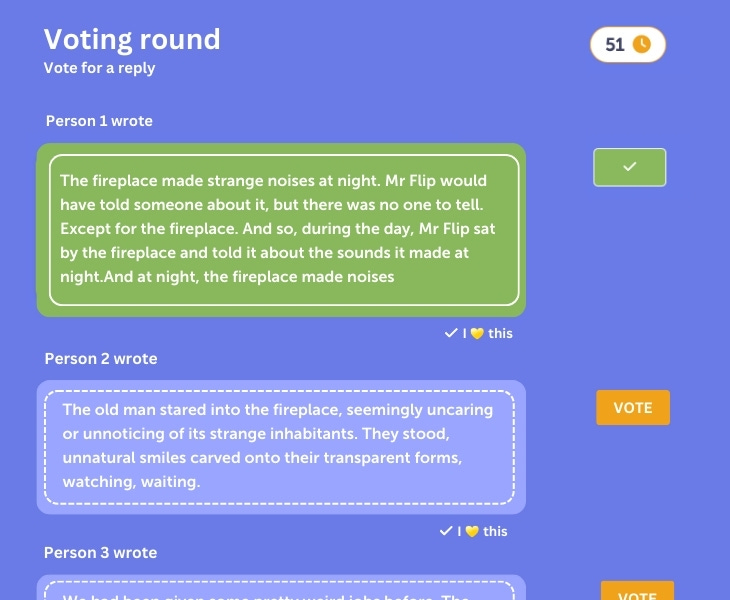

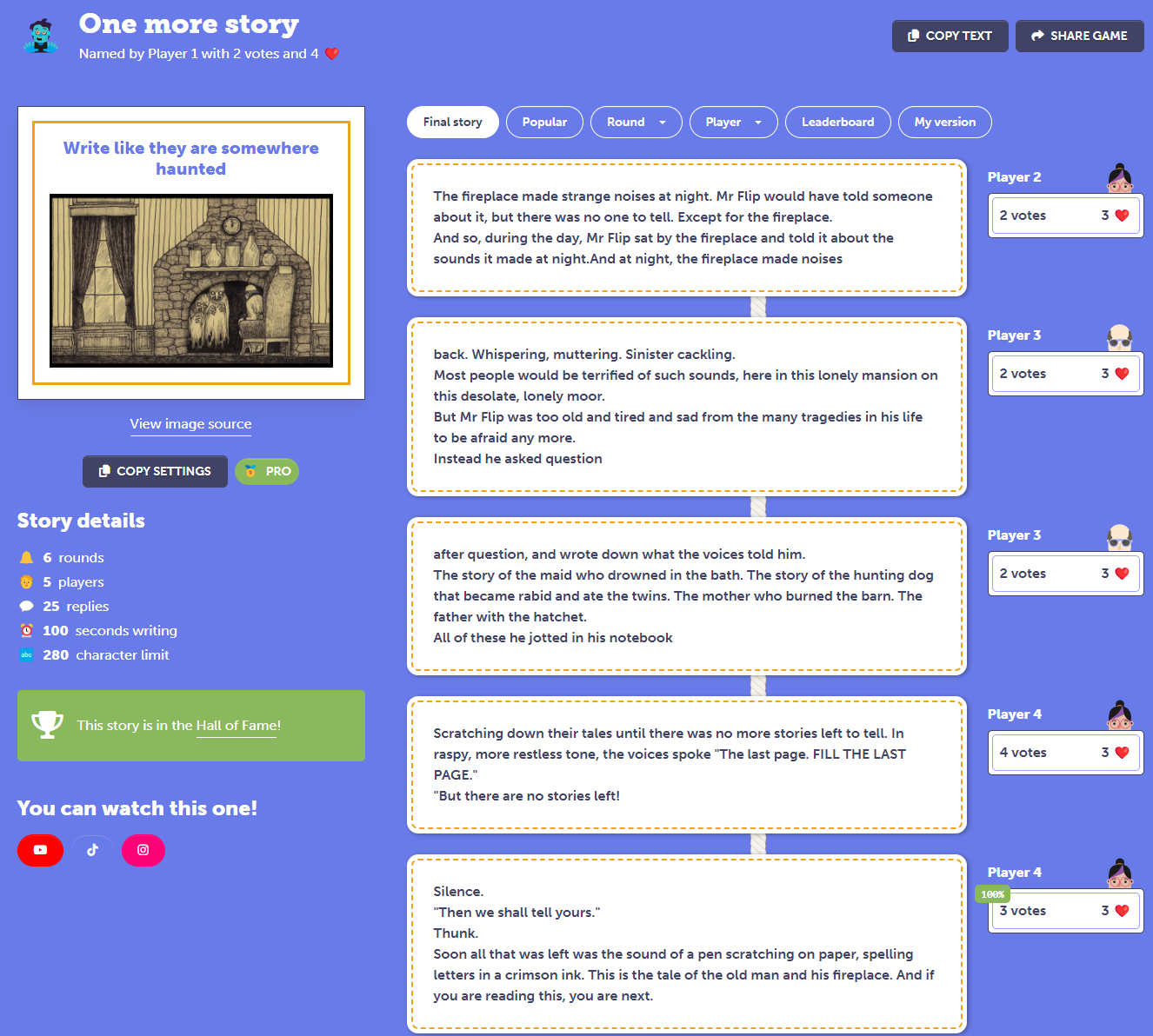

Each game starts with a picture and a prompt which all players write against for a set period of time (e.g. two minutes):

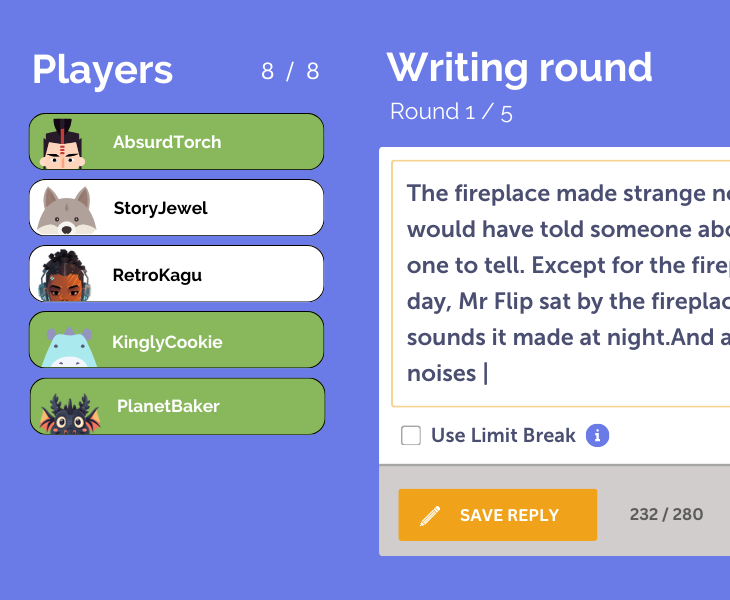

After that there is a round of voting in which players can both like any response they enjoyed, and vote for the entry of another player which they think best captures the story.

Game play continues through a set number of rounds of writing and voting, the story accumulating as each we go. After the final round of writing, there’s a round for choosing a title and the game concludes.

The resulting stories are sometimes brilliant, sometimes absurd or nonsensical, sometimes frustrating, but as someone who is excited to know what students will do when they are given the necessary structure and freedom to write, they’re always interesting.

Truth be told, I traditionally have not been a big fan of the so-called “gamification” of learning. Earning badges and progressing through school like it’s a video game may spur some measure of student buy-in, but to me, it ultimately ends in a behaviorist dead end. The drive toward engagement must be rooted in more enduring stuff.

Frankenstories is a game, but really the game is a structure that gets at multiple dimensions that I believe are important to developing a writing practice.

Demystifying the blank page. Being able to get rolling on a piece of writing is a skill learned through repetition, a skill that is also rooted in habits-of-mind around suspending judgment and understanding writing as a process. Students struggle with this. Everyone struggles with this, but the simplicity and intrigue of the game prompts combined with the timed nature of the entry and the fact that there is really only reward (rather than punishment or judgment) on the other end helps hesitant writers get moving.

Developing taste. One of the underappreciated aspects of developing as a writer is developing one’s “taste,” a sense of both one’s own aesthetics as well as an appreciation for how a piece of writing works on an audience. The voting rounds in a Frankenstories game deliver brief bursts of reflection where players not only judge the writing of others, but have an opportunity to consider how other writers are attempting to solve the same problem they’re wrestling with in a different way.

Developing self-regulation through collaboration. As the folks at Frankenstories can testify, there are students who will take advantage of the opportunity to publicly show off to derail the game, or drag the experience toward their preferences. Over time, though, these behaviors tend not to be rewarded by the group, which becomes invested in having a good experience through the entirety of the game. Playing with other humans requires good, pro-social behaviors, which are rewarded in turn.

Experiencing the benefits of practice. This may sound weird, but in my experience students need to have many more opportunities to look at their own work, and see for themselves how they’ve made progress. I will never forget the student who, after me asking them how they did when they were handing me an assignment they’d been working on for weeks, said, “I’ll let you know after I get my grade.” This is not an attitude directed toward learning, and yet it was the attitude I was fostering with my approach at the time.

I want students to see the difference between achievement (an external marker) and accomplishment (an internal sense of growing capabilities). By practicing writing in an ungraded experience that still has sufficient structure for them to gauge their own progress, students are building important capacities.

Different game prompts tackle different aspects of writing (narrative writing, persuasive writing, informative writing), and even touch on content (Shakespeare), but regardless of the focus of the game, players are practicing their practices, without worrying about grades or performance. They see writing as a vehicle for personal expression where quality and care is rewarded. It is a method of reinforcement far superior to a cycle of assignments to be graded by a teacher alone.

This turned into more of an infomercial for Frankenstories than I intended, so forget about Frankenstories, and consider any kind of educational experience you’ve had from either side of the equation (student or teacher), and I bet you’ll see the benefits of the marriage of structure and freedom to persistence and engagement.

If you have your own assignments or experiences that you feel embody this marriage, please share them in the comments.

Disclosure: I own a very small equity stake in the company that produces Frankenstories. My enthusiasm for the game predates my stake - it’s why I chose to become more involved with them - but readers should know that I do have financial interests in the company.